One of the fairly new APIs added to the web stack is the Navigator.share API. The API allows websites and apps to invoke the native share sheet on OS running the web browser to let the user share text, links and images to the services they actually use.

This week, one of the tasks on our new web app (written in Flutter) was to transition from our custom “share this link” UI that was preconfigured to a select set of services (Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, email) to the native share api allowing users to share the link on their configured services.

Some thoughts on the Share sheet

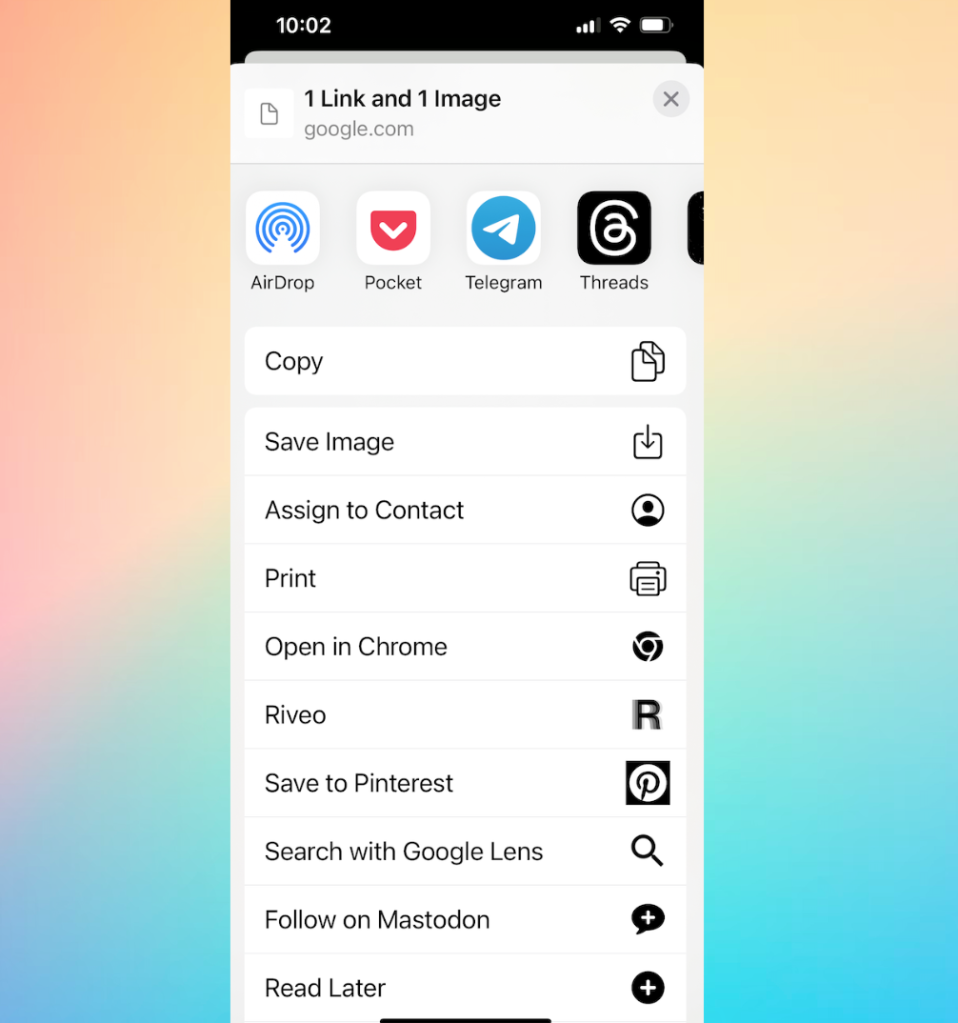

Before I continue, lets talk about the OS share system in general. If there was ever a “God Object” equivalent of user interfaces, the system share sheet on mobile devices has to be it. The widget has become sort of like an escape hatch for the underlying application with not only share capabilities, but a host of other actions in the same menu (Find on page? Print? Add to home screen?) which keeps getting updated by your installed applications. I don’t think anyone can list the menu options there from memory, and yet if we expect to run any action on any data from the underlying application, we expect that action to be available in the share sheet.

I bring this up because the native share from a webpage is now not as simple as sending a title, text, link and image to the share sheet and assuming it would work. Different behaviors from different apps get enabled based on various combination of the 4 fields. For example, one service we wanted to make sure users could use was Instagram (assuming they were Instagram users). IG behavior via share is something like this:

| Input | Instagram behavior |

| Only title, or title + text | Cannot share to Instagram |

| link + any combination of title and text | Share with a friend on Instagram as a message |

| Only image | Share that image in a post, story or message |

| Image + any of the other fields | Share image as a reel |

Other image oriented services like Snapchat and Pinterest also seem to be sensitive to the combination of the 4 fields sent. Its kind of a bummer that we have to now spend QA cycles making sure we are sending the right order of fields to get the desired behavior from the receiving app.

Native share on the desktop?

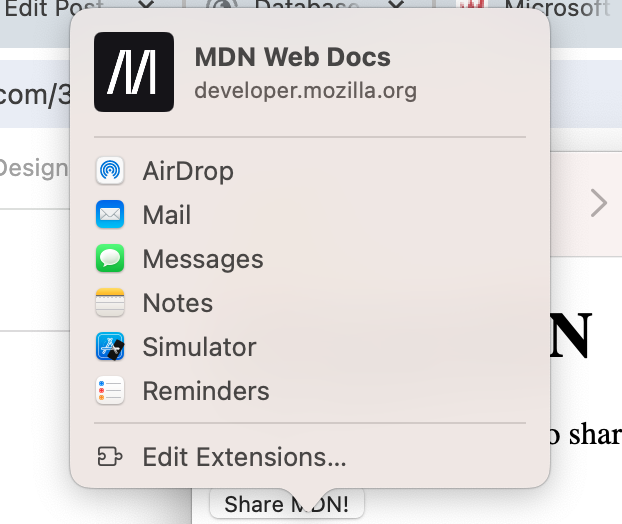

The other challenge to native sharing is that while the browser API may be available on a lot of platforms, native share on the desktop does not make sense since most people don’t install apps for the services they use on their desktop which means that the share menu is pretty barren. Chrome on the Mac desktop, perhaps sensibly, does not support the web share API but Safari does.

Our solution for the app now is to use our custom share UI on desktop browsers but use the native one on mobile. Feels a little hack-ish but it makes the most sense from a user’s point of view.

Sharing images on Flutter web apps with Share Plus

The last aspect of the implementation that tripped us a bit was trying to include images from a web URL along with the title and link to the share API. We are using the Share Plus library which is pretty good and supports the native share API. Unfortunately we didn’t find any links on how to convert an image link to the image attachment (its still early days for Flutter web I suppose). If anyone else needs the snippet, here is how you do it:

final http.Response responseData =

await http.get(Uri.parse(linkToFile));

Uint8List bytes = responseData.bodyBytes;

var file = XFile.fromData( bytes, mimeType: 'image/png', name: "MyPic.png");

await Share.shareXFiles([file], text: 'Hello', subject: 'Check out this image' );

The thing that I wasted 2 hours on today was this snippet not working cause the name I was giving my file did not include the file extension 🤦♂️. So be warned 🙂